Curtiss Aeroplane produced several outstanding racing aircraft during the 1920s, flown by Navy and Army pilots, the latter including First Lt. “Jimmy” Doolittle

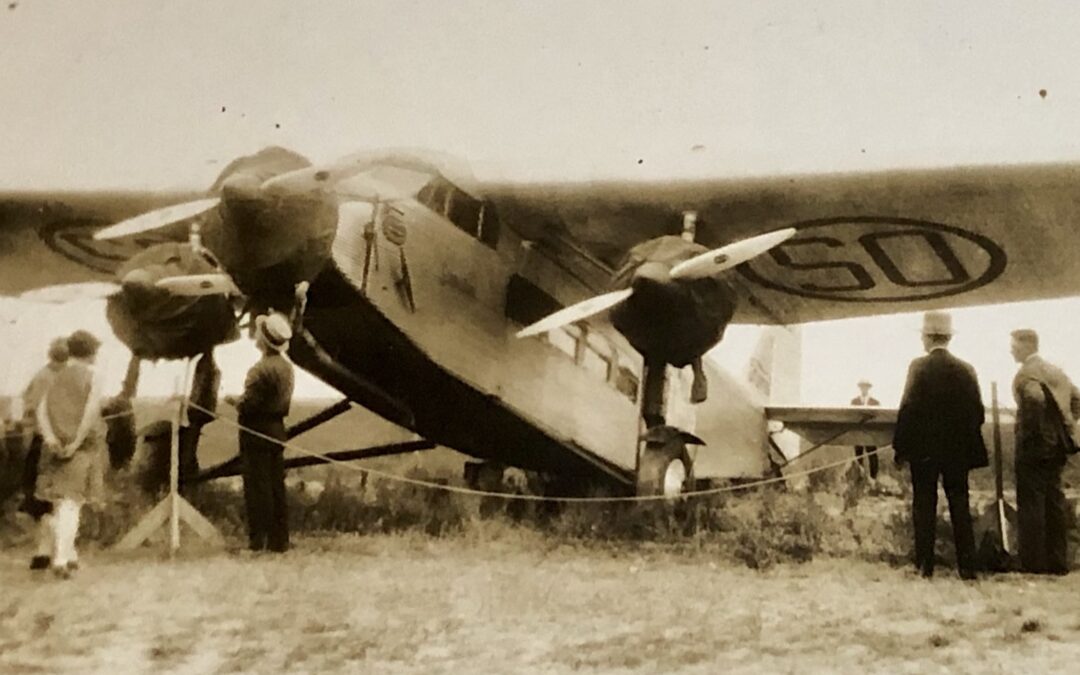

The Army Curtiss Racer in final motor testing, Sept. 16, 1922, at Mitchell Field, in Garden City, N.Y. Lt. Alford J. Williams, U.S.M. (at the tail) and W.L. Gilmore, chief engineer for the Curtiss Co. at the Curtiss Aeroplane development and testing facility. (Photo from the Paul S. Maynard archive)

Just as automobile racing was gaining traction in the years before World War I (1914-18), so was airplane racing. The most famous of these aerial speed contests in the United States and Europe was the international competition known as the Schneider Cup Races.

According to an online report by the U.S. Naval Institute, Jacques Schneider, a wealthy French aero enthusiast, originated the races as a stimulus for seaplane design and the development of overwater flying. The competitions were administered by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale and offered a trophy valued at some $5,000.

The races were for seaplanes and had to be flown entirely over water for a minimum distance of 150 nautical miles. Competitors raced against the clock — not each other — with the fastest average time winning. And the races had to be international.

The first Schneider race was held in 1913, with the United States represented by a privateer. The races were suspended during World War I, then resumed in 1919.

Subsequently, the U.S. military entered the Schneider races three times. The U.S. Navy-Curtiss racers twice won first and second places.

The Pulitzer Trophy Race

In 1921, the Navy decided to compete in the Pulitzer Trophy Race, which the Army had won the previous year. Curtiss was the only major U.S. aircraft firm with prior experience in racer design, and on June 16, 1921, the Navy awarded the firm a contract for two aircraft, though some sources say three planes were built. The Navy had no effective designation scheme, so the aircraft were designated Curtiss Racer (CR) No. 1 and CR No. 2 (which was retained in naval service).

Designed by Mike Thurston and Henry Routh and built at Garden City, Long Island, New York, these were streamlined biplanes with a single, open cockpit. A variety of drag-reducing features were incorporated. Both CRs had wheeled undercarriages, but there were slight differences between the two aircraft.

Their 425-horsepower V-12 Curtiss engines ran on a 50/50 mixture of benzol and gasoline. The water-cooled D-12 had a displacement of 18.8 liters.

Daring Lt. “Jimmy” Doolittle

According to a news story at Airminded.net, the first of the three Curtiss racers (including R3C) was put through its preliminary trials during the week of Sept. 19, 1922.

Alford J. Williams, U.S.M., was to pilot the Navy entry in the Pulitzer Race and Lieut. James H. Doolittle, Army Air Service, flew the plane for short trials to determine airworthiness.

On Sept. 18, Lt. Doolittle, for the first time, opened the throttle wide and flew the actual course of the Pulitzer Race from Mitchel Field, where these tests were carried out. W.L. Gilmore, chief engineer for the Curtiss Company, timed the trials and reported an average speed of 254 mph. for two circuits of the course.

The testing exceeded by approximately 11 mph the last Pulitzer speed figure set up when the Navy Curtiss racer won this race at St. Louis in 1923, clocking 243.6 mph.

The testing at Curtiss’ Garden City plant was considered in every way to be a great achievement in racing airplane design.

The Army went on to win the 1922 Pulitzer race with the new Curtiss R-6 racer, which led the Navy to order two similar aircraft in 1923. Designated R2C-1, these “logical” evolutions of the CRs and R-6s included improved engines that were boosted to 507 horsepower.

On Oct. 6 that year, Navy pilots captured first and second place in the Pulitzer race with speeds of 243.68 mph and 241.77 mph, respectively. Both speeds were later exceeded by those aircraft. In 1923, after the race, one of the R2C-1s was “sold” to the Army for $1 (becoming the Army’s R-8).

Curtiss Aeroplane Legacy

Curtiss produced several outstanding racing aircraft during the 1920s, flown by Navy and Army pilots, the latter including First Lt. “Jimmy” Doolittle.

According to Marine Lieutenant Colonel Robert Rankin of the naval institute:

“Although this country participated officially in the Schneider event for only three years, it did gain considerable technical data from the contests. In addition to the goodwill engendered by the Navy pilots, the races were of positive value in drawing the attention of the general public to our naval air program in the period following World War I when it was all too fashionable to criticize the services. More important, of course, were the research aspects of the contests, the results of which led to many important aircraft improvements and developments.”

NOTE: This is another image from my dad, Paul Smith Maynard, who worked four decades in aviation as an engineer. Dad began his career in about 1943 after graduating from West Virginia University. He started with Curtiss-Wright Corp., an early pioneer in making flying machines. He went on to work at North American Aviation and Rockwell International.

See more of his vintage plane pics here.